Possible Scenarios for Iraq’s New Government’s Formation

Although Iraq’s new government broke the year-long impasse, the road ahead is still paved with difficulties.

On October 13, before the special session of parliament that was to be conducted to elect the new president of Iraq, Iraqis awoke to the sound of nine Katyusha rockets hitting the Green Zone. However, one year after the most recent elections in Iraq, these rockets were not triumphant shots announcing a victory. Security forces attempted to prohibit protesters from entering the Green Zone by blocking all access roads, but they were unable to stop armed factions from expressing their displeasure with Abdul Latif Rashid’s selection as Iraq’s fourth president since the regime’s overthrow in 2003.

Since its Federal Supreme Court ruled in February that the Council of Representatives requires a two-thirds quorum to elect a president, Iraq has experienced total political standstill. By making this decision, the Coordination Framework forces and their supporters were able to unite as an opposition force and prevent the Sadrist Movement and its allies, which included Sunnis and Kurds, from forming a majority-ruling government after the 2021 elections. Instead of a consensus-based government across political groups, the Sadrists had sought to build a majority government, as had been the case during the previous five legislative sessions. The Sadrists finally declined to form a coalition with the Coordination Framework forces after gaining the most seats (73 in total), whom the Sadrists accused of corruption and held responsible for Iraq’s continued problems.

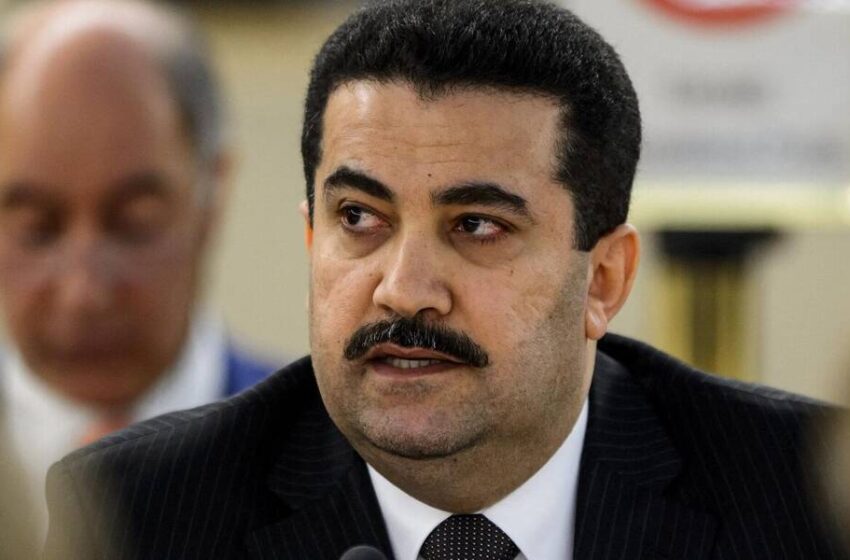

When the Sadrists withdrew from the Council of Representatives, other political forces—the majority of which were in support of the Coordination Framework—came to the fore and began the process of establishing a government. These organizations were successful in forming agreements with previous Sadrist allies, like as Kurds and Sunnis, to choose Rashid as president. Rashid then chose Mohammed Shia al-Sudani to serve as the new prime minister. Despite having left al-Maliki’s party in the past, al-Sudani remains close to the former prime minister. The Sadrists’ efforts to reject a system of political agreement have failed, and the political process in Iraq is resuming normalcy.

The Coordination Framework forces defeated the Sadrists’ efforts, which would have restricted the power to create a new government to the factions that had gotten the most votes, which is how things often work in democracies. However, this would have had two significant effects in Iraq. The majority of political parties and people would have first lost their sway over politics, which would have diminished their power in terms of politics, business, and the military. Second, by keeping Iran’s allies out of the government, it would have robbed Iran of most of its political power over Iraq. This is particularly true given that the Sadrists have been quite clear from the start that they oppose any outside interference in Iraq, whether it comes from Iran, the United States, or any other nation. Additionally, establishing a majority government would have set a precedent that future administrations would need a majority to take office. If that were the case, the forces with little popular support are conscious they would be unable to prevail in subsequent elections.

New political alliances and agreements were formed with the Sadrists gone but the Coordination Framework still failing to attain a two-thirds quorum. Former Sadrist supporters took advantage of the Framework’s need for backing and raised their expectations in exchange for joining the coalition and creating a government, especially the Sunnis and Kurds. One of these requests was Masoud Barzani’s insistence that Barham Salih, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) candidate, be barred from running for president and instead be replaced by either a representative of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) or a new PUK candidate.

Additionally, the Coalition Framework forces conceded to a number of Kurdish and Sunni demands that they had previously been unwilling to discuss, particularly in relation to the oil and gas in the Kurdistan Region, Article 140 of the constitution—which established the Kirkuk status referendum—and the removal of de-Baathification tools that had been used against Sunnis.

However, since both the Sadrists and the October/Tishreen Movement had previously opposed the nomination of al-Sudani as prime minister, it is unclear how the two major players in Iraq’s political scene will react now that the president has been chosen and a candidate for prime minister has been selected.

The October Movement, which forced former Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi to resign and compelled the previous Council of Representatives to alter the electoral law, has now lost a lot of its momentum as a result of being a primary target for misinformation and physical attacks from militias and pro-Iranian forces in Iraq. Splintering of these forces and subsequent momentum loss was also a result of internal arguments over leadership and ideologies within the Movement as well as conflicts with the Sadrists. Despite pledges made to the October Movement by al-Kadhimi’s government, al-Khadimi has failed to deliver and has even attempted to appease armed parties opposed to the October Movement in the expectation that they will support him in the next elections. Al-Kadhimi did not want the October Movement to cause problems for his government by denouncing corruption, injustice, a lack of social services, and a loss of sovereignty.

However, even if the movement has lost a lot of its vigor, the majority of Iraqis, especially the young, still hold the movement’s beliefs dear. Everyday Iraqis are still aware of what was accomplished in 2019–2020, which continues to terrify political parties in power. There were calls for bigger action, and while if fewer people than anticipated took to the streets on the third anniversary of the October uprising, it is still possible to plan a larger demonstration for October 25. The election of al-Sudani as prime minister will present a fresh obstacle to the goals of the October Movement. Al-Sudani was a politician who the October Movement had previously opposed because of his close ties to al-Maliki and who had previously been proposed by pro-Iranian forces during the October uprising. Whether these incidents will lead young people in Baghdad and southern Iraq to oppose the government more remains to be seen.

Al-Sadr and his large support base are also personally challenged by al-Sudani’s nomination. Like the October Movement, al-Sadr had previously opposed al-Sudani’s nomination. Several months earlier, a representative for al-Sadr on social media even shared a tweet poking fun at al-Sudani’s nomination because of his ties to al-Maliki, one of al-Sadr’s main political rivals. Now, everyone is wondering how al-Sadr will react to this nomination. At this point, it appears that three scenarios are most plausible. Al-Sadr might first keep quiet about the nomination to allow al-Sudani to form his cabinet, and then after letting al-Sudani a few months to prove his mettle, he could rally his people. According to the Sadrists’ assessment, if al-Sudani fails, they could organize a public movement to have him overthrown.

Most analysts did not anticipate to see Al-Sadr remain silent over al-Sudani’s nomination. Nevertheless, issues with the selection of a government are sure to arise, with provocations from the Coordination Framework that will unavoidably enrage the Sadrists. The Sadrists won’t be able to remain silent for very long as a result of this. Additionally, the Sadrists may use this moment of transition as an opportunity to become involved before Framework forces seize control of state institutions, particularly the security forces, who would be opposed to any peaceful protest movement. Naturally, this scenario could also result in political dissension within the Sadrist movement.

In a second scenario, the forces of the Coordination Framework might be able to placate the Sadrists by giving them some cabinet positions, future pledges of early elections, or even the power to reject Coordination Framework cabinet members. Based on what al-Sadr has previously indicated, this situation doesn’t seem to be particularly realistic. To those closest to him, he made it clear that he did not wish to engage in covert negotiations with Coordination Framework forces. As an instance, the same al-Sadr social media representative tweeted a few days earlier that Sadr would not permit any of his loyalists to serve in the new cabinet.

The likelihood of the third scenario is the highest. In this case, the Sadrists would hold public protests and obstruct the establishment of the new government by waiting until the ideal opportunity, such as the third anniversary of the October revolt on October 25, 2022, or a comparable event. There are rumors that the leaders of the October Movement and Sadrists have been in talks to reach agreements in order to coordinate their operations and gather resources for a significant popular movement to overthrow the regime.

There is no doubt that the splits among the Coordination Framework forces, which became apparent during the choice of the new president, will become more entrenched if a popular alliance between the Sadrists and the October Movement is effective. The Coordination Framework will be divided between “doves,” like Haider al-Abadi, who will insist on placating al-Sadr and oppose forming the new administration, and “hawks,” who will once more turn to deploying militias to quell a popular uprising. Armed conflict is still possible unless political and religious groups succeed in preventing firearms from reaching non-state actors, like Ayatollah al-Sistani. Even if the new administration is successful, it will undoubtedly face numerous obstacles, making al-Sudani’s work nearly impossible. Will al-Sudani accomplish this “mission impossible” and become the Tom Cruise of Iraq? We won’t have to wait long to learn the answer.

for more news, visit us on iraq2english.com